I met Santan Monteiro at her stall outside the Mount Mary church last month. It was a chance meeting that summer day since Krishna and I hadn’t planned on visiting the church when we landed in Bandra on a late May afternoon. We didn’t expect our walkabout in Waroda and Ranvar to finish early, leaving enough time on our hands for a quick visit to the Mount Mary church. There, Santan Monteiro smiled at me when I stepped into her stall with my camera. As we got talking, she told me that she hails from Verna, in Goa. I asked her if she manages to visit Goa. She said, "Yes. yes. I do." Then she told me that she will be visiting Saligao (a Goan town) the next month, in June. “I visit Goa once a year to meet my relatives,” she added.

It was early evening when we took the turn past the Bandra Bandstand on our way to the Mount Mary Church in Bandra. The monsoon was three weeks away but clouds straggled across the sky from the west, in ones, twos, and threes, sometimes more. In days to come more would follow. The rickshaw laboured up the hill, flanked on either side by residential high-rises and bungalows that sat pretty facing the sea a short distance away. I read Parsi names on a building or two. I like Parsi names. Jeejabhoy, Merchant, Taraporewalla, Daruwalla. As we motored up, every once in a while I saw people gathered on terraces facing the sea, gazing fixedly at the ocean. There is something about vast landscapes that I find soothing, so vast that there is no single point of focus to gather my attention to the exclusion of others. Sometimes, I find that vastness showcases a sameness that offers me a continuity that is absent in closed spaces, ‘closed’ as in by structures which even if diverse do not intrigue me like vastness does since they have forms I can identify, and relate to. Vastness has no form; it is continuous, end-to-end.

Mid-way up the hill, the road narrowed; I cannot quite remember if it was because of a tree, or on account of road repairs. Vehicles coming down the slope showed little consideration for those going up the incline, blocking way and forcing us into braking, losing momentum. The rickshaw stalled in its attempt to drag us up the incline, it had lost power, eventually I asked the driver to return to the base of the hill and give it another shot up. We turned back and rode down, and waited until there was no vehicle coming down the hill and gave it full power. He left us on the road passing by the Mount Mary church.

Outside the church, stalls selling candles and wax dolls line the compound wall enclosing the church on either side of the narrow entrance leading up to the church. The compound wall has the same feel as the façade of the church, made of stones demarcated by white lines. From a distance I imagine it must look like someone has draped a checked shirt over it. The church is dedicated to Christ’s mother, Virgin Mary, whose statue Jesuit priests brought from Portugal in the 16th century and constructed the chapel on the mount in 1640 where they housed it. The church was rebuilt in 1761 after the original Chapel of Mount Mary was destroyed in what is believed to be a Maratha raid in 1738. The statue of Mother Mary was shifted back to the rebuilt church from St. Andrews church where it was temporarily installed after fishermen found it in the sea. The original statue was re-adorned with the child in her arms after marauding Arab pirates cut off the hand to get at the gilt-lined figure of the child in her arms.

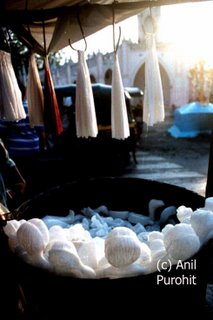

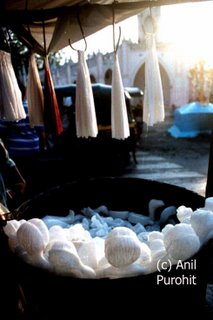

Santan Monteiro was alone in her stall. She was dressed in a frock and had a kind face. When I first met her on alighting in front of the church, I had a feeling she was originally from Goa. Time had etched its passage on her face. Hers was a makeshift stall. Candles coloured white, dark blue, light blue, red, and orange, hung from hooks looped around a horizontal bamboo support held up by bamboos fixed to the ground. In a basket by her side, wax figures shaped as hands, legs, spine, head and other parts of the human body were neatly stacked along the circumference of the rim. Actually, some of them were reclining as if resting easy while enjoying the view of the sun going down. The setting sun opposite lit them up in a translucent white. Devotees who come to Mount Mary to pray for cures for their ailments offer the wax figure that corresponds to their ailment. “Here, this one is for the stomach,” said Santan Monteiro, showing me a circular plate-like wax figure. “A patient suffering from a stomach ailment will offer it at the church by setting it alight, and saying prayers.” Then she held out a wax figure shaped like a back and said, “This one is for a back ailment.” As we talked in konkani, a steady stream of devotees came up to her stall to purchase candles, and the wax figures that she refers to as baulis (bauli is konkani for doll). Devotees belong to all religions, and their belief in Mother Mary’s powers to affect miracles is absolute, drawing them to the church from long distances. On the Sunday following September 8, the Bandra fair is held each year in the honor of Mother Mary. It carries on for eight days amidst much fanfare and piety.

In a basket by her side, wax figures shaped as hands, legs, spine, head and other parts of the human body were neatly stacked along the circumference of the rim. Actually, some of them were reclining as if resting easy while enjoying the view of the sun going down. The setting sun opposite lit them up in a translucent white. Devotees who come to Mount Mary to pray for cures for their ailments offer the wax figure that corresponds to their ailment. “Here, this one is for the stomach,” said Santan Monteiro, showing me a circular plate-like wax figure. “A patient suffering from a stomach ailment will offer it at the church by setting it alight, and saying prayers.” Then she held out a wax figure shaped like a back and said, “This one is for a back ailment.” As we talked in konkani, a steady stream of devotees came up to her stall to purchase candles, and the wax figures that she refers to as baulis (bauli is konkani for doll). Devotees belong to all religions, and their belief in Mother Mary’s powers to affect miracles is absolute, drawing them to the church from long distances. On the Sunday following September 8, the Bandra fair is held each year in the honor of Mother Mary. It carries on for eight days amidst much fanfare and piety.

About then a middle-aged couple steps up to Santan Monteiro’s stall asking her in hindi if they should offer the wax bauli at the church now or after they get a house. I listen on for I never tire of a Goan Catholic attempting hindi. It does not matter if they’ve lived in Mumbai for years, like Bandra’s Christians with roots in Goa, have, their Hindi shows the influence of konkani, lacing it with an edge that people up North would find a touch arrogant, insulting even. She advises them to offer prayers at the church for the house they hope to own someday, and return to the church to offer the wax bauli after their prayers are answered. “We prepare all these wax items at home,” she told me, “using molds.

“Baba accha sa pass hone ka,” (Baba should pass his exams well) she said to the same couple who mentioned about their son who was appearing for his exams. “You can pray for him at the church now, then offer a wax-book after he does well in his exams,” she told them. On a wooden plank near the front of the stall, she had stacked packets of gram. “My mother-in-law started this business fifty years ago,” she told me, running her hand in an arc indicating the stall she ran on her own. “She supported the entire family from her earnings from this stall. She is originally from this place. After I got married and came to Bombay, I helped her run this stall.”

I ask her how old is she.

“Sixty. To sixty, add three more,” she replied.

“Sixty-three?”

“Yes,” she said, smiling.

Santan Monteiro lives in Bandra. Then she told me of her children and her grand-children. I listened on, pausing only when customers stopped by her stall to make purchases, watching her treat them kindly and answer their queries patiently. The sun cast golden shafts our way, lighting up the stall in a soft memory.

I purchased candles for five rupees, thanked her and said that I would return to her stall with copies of her photographs. She smiled back, nodding her head.

Then, Krishna and I walked across the road, and took the stairs up to offer our prayers at the statue of Mother Mary. Candles and wax figures blazed bright on a metal stand where a steady stream of devotees set them alight in the flame, then folding their hands they offered prayers at the statue of Mother Mary. Behind her, the sun dipped low. A temple tree bloomed with a vengeance nearby. I bent over the wall to try and pluck a flower but couldn’t get close enough, but managed to get near enough to catch the fragrance wafting from the white and gold flowers I once lived with in my backyard years ago before we shifted to a new house.

Santan Monteiro was alone in her stall. She was dressed in a frock and had a kind face. When I first met her on alighting in front of the church, I had a feeling she was originally from Goa. Time had etched its passage on her face. Hers was a makeshift stall. Candles coloured white, dark blue, light blue, red, and orange, hung from hooks looped around a horizontal bamboo support held up by bamboos fixed to the ground.

In a basket by her side, wax figures shaped as hands, legs, spine, head and other parts of the human body were neatly stacked along the circumference of the rim. Actually, some of them were reclining as if resting easy while enjoying the view of the sun going down. The setting sun opposite lit them up in a translucent white. Devotees who come to Mount Mary to pray for cures for their ailments offer the wax figure that corresponds to their ailment. “Here, this one is for the stomach,” said Santan Monteiro, showing me a circular plate-like wax figure. “A patient suffering from a stomach ailment will offer it at the church by setting it alight, and saying prayers.” Then she held out a wax figure shaped like a back and said, “This one is for a back ailment.” As we talked in konkani, a steady stream of devotees came up to her stall to purchase candles, and the wax figures that she refers to as baulis (bauli is konkani for doll). Devotees belong to all religions, and their belief in Mother Mary’s powers to affect miracles is absolute, drawing them to the church from long distances. On the Sunday following September 8, the Bandra fair is held each year in the honor of Mother Mary. It carries on for eight days amidst much fanfare and piety.

In a basket by her side, wax figures shaped as hands, legs, spine, head and other parts of the human body were neatly stacked along the circumference of the rim. Actually, some of them were reclining as if resting easy while enjoying the view of the sun going down. The setting sun opposite lit them up in a translucent white. Devotees who come to Mount Mary to pray for cures for their ailments offer the wax figure that corresponds to their ailment. “Here, this one is for the stomach,” said Santan Monteiro, showing me a circular plate-like wax figure. “A patient suffering from a stomach ailment will offer it at the church by setting it alight, and saying prayers.” Then she held out a wax figure shaped like a back and said, “This one is for a back ailment.” As we talked in konkani, a steady stream of devotees came up to her stall to purchase candles, and the wax figures that she refers to as baulis (bauli is konkani for doll). Devotees belong to all religions, and their belief in Mother Mary’s powers to affect miracles is absolute, drawing them to the church from long distances. On the Sunday following September 8, the Bandra fair is held each year in the honor of Mother Mary. It carries on for eight days amidst much fanfare and piety.About then a middle-aged couple steps up to Santan Monteiro’s stall asking her in hindi if they should offer the wax bauli at the church now or after they get a house. I listen on for I never tire of a Goan Catholic attempting hindi. It does not matter if they’ve lived in Mumbai for years, like Bandra’s Christians with roots in Goa, have, their Hindi shows the influence of konkani, lacing it with an edge that people up North would find a touch arrogant, insulting even. She advises them to offer prayers at the church for the house they hope to own someday, and return to the church to offer the wax bauli after their prayers are answered. “We prepare all these wax items at home,” she told me, “using molds.

“Baba accha sa pass hone ka,” (Baba should pass his exams well) she said to the same couple who mentioned about their son who was appearing for his exams. “You can pray for him at the church now, then offer a wax-book after he does well in his exams,” she told them. On a wooden plank near the front of the stall, she had stacked packets of gram. “My mother-in-law started this business fifty years ago,” she told me, running her hand in an arc indicating the stall she ran on her own. “She supported the entire family from her earnings from this stall. She is originally from this place. After I got married and came to Bombay, I helped her run this stall.”

I ask her how old is she.

“Sixty. To sixty, add three more,” she replied.

“Sixty-three?”

“Yes,” she said, smiling.

Santan Monteiro lives in Bandra. Then she told me of her children and her grand-children. I listened on, pausing only when customers stopped by her stall to make purchases, watching her treat them kindly and answer their queries patiently. The sun cast golden shafts our way, lighting up the stall in a soft memory.

I purchased candles for five rupees, thanked her and said that I would return to her stall with copies of her photographs. She smiled back, nodding her head.

Then, Krishna and I walked across the road, and took the stairs up to offer our prayers at the statue of Mother Mary. Candles and wax figures blazed bright on a metal stand where a steady stream of devotees set them alight in the flame, then folding their hands they offered prayers at the statue of Mother Mary. Behind her, the sun dipped low. A temple tree bloomed with a vengeance nearby. I bent over the wall to try and pluck a flower but couldn’t get close enough, but managed to get near enough to catch the fragrance wafting from the white and gold flowers I once lived with in my backyard years ago before we shifted to a new house.

Reading your narration brings forces of reminiscence along. What nostalgia it bears on the mind of the reader! Little happenings like such that one would not expect others to have experienced, or to have paid attention to, as well. Thank You.

ReplyDeleteBrilliant ! Anil, your posts are so evocative, sometimes you don't even need the snaps..but then your snaps are great as well ! Thanks for a lovely post.

ReplyDeleteI'm so glad i saw this!

ReplyDeleteI just watched Amar, Akbar, Anthony Sunday and saw this church in it.

Thanks!

To Kizzy: Thanks. Very true. Sometimes, reminiscence is triggered by a face, a place, and occasionally time. It is little things that help us with perspectives. Little is indeed big!

ReplyDeleteTo Bombay Addict: Thanks. Mumbai corners are interesting places indeed. They evoke footfalls that've long disappeared. And in their echo the new ones (like mine) meander in search of memories :)

To Filmiholic: That was one unforgettable movie. The story behind the name 'Anthony' makes for interesting reading. :)

ive lived at mount mary all ma life n i jst moved to canada.

ReplyDeletebut seriously ders no place in d wrld dat b like ours v shud b soo proud to b indians.n dat tooo livin in suchhaa beautiful place.

may bandra keep rockin like aways.

thnx for ur article brought soo mny memories!!!!

The pics were a feast for the eyes. tx for sharing them.....gosh sometimes i wonder where have I been !!

ReplyDeleteOnly sadness fills me when I visit this church, I had two events. The memories, I wish were happier, however are sad for me. God Bless you.

ReplyDeleteHi Windy skies,

ReplyDeleteI'd like to grab parts of this story for one of my articles....hope thats ok by you. Its few notes about Satan Monteiro that I wanna feature when writing about Mount Mary Church in the article

The topic goes - 5 things without which Bandra wouldnt be Bandra

This is for our student tabloid - FRIDAY that is issued by MET Institute of Mass Media, Bandra

Hi Anon: Thanks for communicating the same to me, I appreciate your gesture. You could mention Santan Monteiro from the blog piece.

ReplyDeleteIf you can credit the WindySkies blog as a source that would be great.