On our drive past Sindgi enroute to Havalgi through Almel, before passing Afzalpur in the Bijapur district of North Karnataka, the road had not changed character from years ago. Until then, after the night halt at my relative’s place in Bijapur, the drive had been dream-like, with scarcely a bump in the road. Actually, it had been a revelation.

It was beyond Sindagi that I truly woke up that April morning as the jeep bumped and swerved on the road. I looked out the window to watch vast fields inch past in a sepia downpour of the familiar. That familiar mud, dark brown, freshly ploughed, brought memories of another day from another age flooding in.

This road used to be my cycling route in my vacations from school. Though I never managed to cycle the twenty kilometers that separates Almel from Sindgi for, cycling forty kilometers to and fro in the heat of summer meant a certain heatstroke, I regularly cycled ten kilometers of the stretch, enjoying the breeze before cycling back the way I had come. Dodging cattle on their way back from their grazing grounds, dismounting to make way for buses plying the route (Almel is eighty kilometers from Bijapur) between Bijapur and Gulbarga, racing bullock carts and waving out to farmers out in the fields served to make twenty kilometers of cycling rest easy on my knees. It helped me sleep easy on the terrace under the stars while the massive Peepal opposite brooded over me. I loved riding with the clouds, and in those landscapes of North Karnataka one can ride long distances with the clouds without losing sight of your nameless companions in the sky.

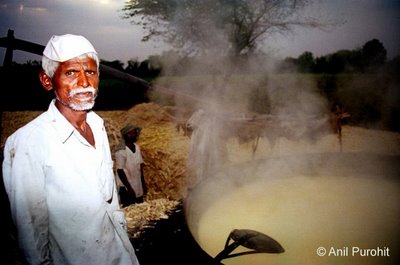

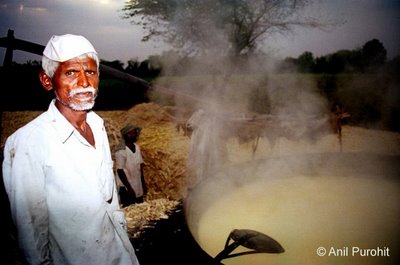

Every once in a while in the summer after a particularly furious bout of pedaling, I pulled up to the side of the road and walked across the field where farmers were extracting sugarcane juice to make jaggery. They offered me juice in brass jugs, filling it up until I had enough. Then it was time to pedal back to the calls of the Brahminy Starling and Mynahs. So when we passed trails of smoke emerging from the fields a few kilometers before Almel, smelling sweetly of sugarcane extracts, we pulled up to the side of the road and walked across Poddar’s sugarcane field to find Basanna tending to a large kadai (a large, wide metal utensil used for boiling extracts) filled with sugarcane juice. Behind him two farmers were crushing sugarcane in a cane crusher while the juice ran down a conduit to an open, circular pit in the ground. They had filled the kadai with sugarcane extract and placed it on an opening in the kiln while a low fire fueled by leftovers of crushed sugarcane fueled the kiln, manned by a farmer who stood by, watching the fire through an opening in the mud and brick construction.

Basanna was clad in a dhoti and a Gandhi topi, the attire common to older generation of farmers in that belt. He’s been working on the farm for over twenty years and told us that sugarcane extraction begins post-Diwali. The kiln was set up at ground level over a largish area, now turned white with leftovers of crushed sugarcane. Underground piping carried the exhaust to a bottle shaped chimney about seven feet tall, constructed a short distance away from the heat source over which the kadai, filled with sugarcane juice was placed. The kadai held over 950 litres of sugarcane juice, a white simmering mass.

Basanna was clad in a dhoti and a Gandhi topi, the attire common to older generation of farmers in that belt. He’s been working on the farm for over twenty years and told us that sugarcane extraction begins post-Diwali. The kiln was set up at ground level over a largish area, now turned white with leftovers of crushed sugarcane. Underground piping carried the exhaust to a bottle shaped chimney about seven feet tall, constructed a short distance away from the heat source over which the kadai, filled with sugarcane juice was placed. The kadai held over 950 litres of sugarcane juice, a white simmering mass.

It is boiled for over two hours before it is transferred to a rectangular holding area in a shed adjacent to the kiln where it is left to cool before it is poured into metal buckets to shape the resulting jaggery into cone shaped blocks, each weighing 15 kilos. We saw a few lined up along the length of the makeshift shed. It takes 950 litres of sugarcane juice to produce 11-12 such cone shaped blocks (called penti in the local language Kannada) of jaggery. Later they are shipped to the market. "950 litres of sugarcane extract will yield about 200 kilos of jaggery," Basanna said.

We saw a few lined up along the length of the makeshift shed. It takes 950 litres of sugarcane juice to produce 11-12 such cone shaped blocks (called penti in the local language Kannada) of jaggery. Later they are shipped to the market. "950 litres of sugarcane extract will yield about 200 kilos of jaggery," Basanna said.

The farmers work through the day, starting at the break of day at 6 am, and continuing till six in the evening. Basanna happened to know my uncle from Almel well, and we exchanged smiles that only familiarity can induce. We carried back sugarcane juice in empty softdrink bottles for the road. Havalgi was still fifty-odd kilometres away. While on our way out I peeked inside a fairly deep well hewn out of the earth nearby before dodging a sleeping form wrapped in colourful quilt (called dhubti in the local language), lost to the world in a mass of crushed sugarcane leftovers that early morning.

The sun was breaking out in the distance as we hit the road again.

It was beyond Sindagi that I truly woke up that April morning as the jeep bumped and swerved on the road. I looked out the window to watch vast fields inch past in a sepia downpour of the familiar. That familiar mud, dark brown, freshly ploughed, brought memories of another day from another age flooding in.

This road used to be my cycling route in my vacations from school. Though I never managed to cycle the twenty kilometers that separates Almel from Sindgi for, cycling forty kilometers to and fro in the heat of summer meant a certain heatstroke, I regularly cycled ten kilometers of the stretch, enjoying the breeze before cycling back the way I had come. Dodging cattle on their way back from their grazing grounds, dismounting to make way for buses plying the route (Almel is eighty kilometers from Bijapur) between Bijapur and Gulbarga, racing bullock carts and waving out to farmers out in the fields served to make twenty kilometers of cycling rest easy on my knees. It helped me sleep easy on the terrace under the stars while the massive Peepal opposite brooded over me. I loved riding with the clouds, and in those landscapes of North Karnataka one can ride long distances with the clouds without losing sight of your nameless companions in the sky.

Every once in a while in the summer after a particularly furious bout of pedaling, I pulled up to the side of the road and walked across the field where farmers were extracting sugarcane juice to make jaggery. They offered me juice in brass jugs, filling it up until I had enough. Then it was time to pedal back to the calls of the Brahminy Starling and Mynahs. So when we passed trails of smoke emerging from the fields a few kilometers before Almel, smelling sweetly of sugarcane extracts, we pulled up to the side of the road and walked across Poddar’s sugarcane field to find Basanna tending to a large kadai (a large, wide metal utensil used for boiling extracts) filled with sugarcane juice. Behind him two farmers were crushing sugarcane in a cane crusher while the juice ran down a conduit to an open, circular pit in the ground. They had filled the kadai with sugarcane extract and placed it on an opening in the kiln while a low fire fueled by leftovers of crushed sugarcane fueled the kiln, manned by a farmer who stood by, watching the fire through an opening in the mud and brick construction.

Basanna was clad in a dhoti and a Gandhi topi, the attire common to older generation of farmers in that belt. He’s been working on the farm for over twenty years and told us that sugarcane extraction begins post-Diwali. The kiln was set up at ground level over a largish area, now turned white with leftovers of crushed sugarcane. Underground piping carried the exhaust to a bottle shaped chimney about seven feet tall, constructed a short distance away from the heat source over which the kadai, filled with sugarcane juice was placed. The kadai held over 950 litres of sugarcane juice, a white simmering mass.

Basanna was clad in a dhoti and a Gandhi topi, the attire common to older generation of farmers in that belt. He’s been working on the farm for over twenty years and told us that sugarcane extraction begins post-Diwali. The kiln was set up at ground level over a largish area, now turned white with leftovers of crushed sugarcane. Underground piping carried the exhaust to a bottle shaped chimney about seven feet tall, constructed a short distance away from the heat source over which the kadai, filled with sugarcane juice was placed. The kadai held over 950 litres of sugarcane juice, a white simmering mass.It is boiled for over two hours before it is transferred to a rectangular holding area in a shed adjacent to the kiln where it is left to cool before it is poured into metal buckets to shape the resulting jaggery into cone shaped blocks, each weighing 15 kilos.

We saw a few lined up along the length of the makeshift shed. It takes 950 litres of sugarcane juice to produce 11-12 such cone shaped blocks (called penti in the local language Kannada) of jaggery. Later they are shipped to the market. "950 litres of sugarcane extract will yield about 200 kilos of jaggery," Basanna said.

We saw a few lined up along the length of the makeshift shed. It takes 950 litres of sugarcane juice to produce 11-12 such cone shaped blocks (called penti in the local language Kannada) of jaggery. Later they are shipped to the market. "950 litres of sugarcane extract will yield about 200 kilos of jaggery," Basanna said.The farmers work through the day, starting at the break of day at 6 am, and continuing till six in the evening. Basanna happened to know my uncle from Almel well, and we exchanged smiles that only familiarity can induce. We carried back sugarcane juice in empty softdrink bottles for the road. Havalgi was still fifty-odd kilometres away. While on our way out I peeked inside a fairly deep well hewn out of the earth nearby before dodging a sleeping form wrapped in colourful quilt (called dhubti in the local language), lost to the world in a mass of crushed sugarcane leftovers that early morning.

The sun was breaking out in the distance as we hit the road again.

You have done it again, Anil. I truly adore your ability to replay memories with such fluid words and almost no effort! This post gives a very good feeling. More so because of your childhood connection. Well done, and keep posting!

ReplyDeleteTo Mercurian: Thanks. It's a pleasure to revisit familiar terrain, more so since they were my cycling routes of my carefree school days. Actually, those vacations never really ended, I play them in my mind every once in a while :)

ReplyDeleteNice to read this one! Reminds me of my good ole' days of childhood. I grew up in Shimoga, and I used to look forward to the days when sugarcane is ripe and ready to be cut and made into juice and jaggery. We would rush to the 'Alemane' for the treat. And I never foret the smell and taste of fresh jaggery!

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting!

your writing holds transient life in words—there is so much more of life that only words can convey....

ReplyDeleteTo Arun: Thanks. I can well understand what it is to remember those sugarcane days. I remember my school days travelling by KSRTC buses through North Karnataka at night, passing tractor after tractor loaded with sugarcane. There were hundreds of them passing us in the night. Occasionally, reaching out the window of the bus, I would pluck a sugarcane or two that I could get hold of. Those were the sweetest sugarcane I ever tasted on my journeys through that magnificient countryside.

ReplyDeleteTo Anany: Thank you. Sure, life has lots to offer. It always did.

...I would pluck a sugarcane or two

ReplyDeleteI always imagined doing that, but never actually managed to do it.. :)

I have a very strong urge of eating jaggery or penty now reading this :)

ReplyDeleteI have never seen anything like this, besides I hardly have travelled much.

To Arun: The trick is, to wait for a tractor trailer packed high with sugarcane passing you in the opposite direction, then lean out the window of the bus and latch onto one sugarcane near the top of the pile, and hold on to it, tight. Soon enough, the sugarcane pulls free as the bus moves ahead, and so also the tractor, in the opposite direction. Then it is time to share it with co-passengers, a surefire way to make friends in the bus, beside some delicious munching :)

ReplyDeleteTo Kusum: Out there in the fields where it is made, jaggery tastes the best. Try it someday :)

Nice to read the post. Reminds me of my childhood days around country side of Gulbarga. Keep posting.

ReplyDeleteThanks.

Venkatesh

To Venkatesh: Thanks. Sure will.

ReplyDeleteHi Sachin,

ReplyDeleteYeah, I can well imagine. Out there it is a pleasure to visit places where time hasn't moved much. I suppose it is where we can catch up with times past.

hey!! interesting bits on the sugarcane. we used to have a small sugarcane plantations near in Ulhalli, near Nanjangud (mysore). i remember the time, (i as not a child anymore!) when i used to love chewing juicy pieces of cane, all nealty cleaned out and given to me ofcourse. digging in my city teeth into the fleshy stem!! neevr figured out what made jaggery so wonderful or sugar so sweet. must be the hard work, i think. i also rememebr the cuts in my mouth when i tried to pull the skin with my teeth.

ReplyDeleteyour accounts of jaggery making was useful. now am a writer and write ll sorts of things. perhaps i could use some of it "processes of jaggery making!!!)

To Anjaly: Thank you. Rural Karnataka hosts many such landscapes, and those sugarcane fields rank near the top for the activity one gets to see in the sugarcane season. Roads that pass by those fields smell intoxicatingly different from the process of making Jaggery.

ReplyDeleteIts very gr8 to read abt the Area I hav visited often. But the Karnataka Govt has done very little development in this area.

ReplyDeleteWhile travelling from Gulbarga to Sholapur,via Ganagapur and Akkalkot, One can really feel the development that the Maharashtra govt has done in this area, and also feel sorry that Karnataka govt has done nothing. If Karnataka govt can do nothing, Let this area go to Maharashtra ... Atleast people can see development. There is no point in having false pride for karnataka.

Raj S: I have fond memories of this place, and that includes the language, the people in general, and the landscape.

ReplyDeleteMaybe there is no development of the kind you say, but if they can straighten the road, provide for good health facilities, and water and electricity the place should be ok.

I just hope it does not go the way many places have, riding on land mafias and mindnumbing commercialisation.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteSmitha Sindagi: Thank you :)

ReplyDeleteit is dr shetty @ mumbai from sindgi.i really was wondering if this is the description of our area.

ReplyDeletereally mind blowing.

keep blogging.

Dr. Shetty: Yes, North Karnataka. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteIt was nice reading about alemane and memories attached to it. I am linking it to one of my posts on my blog :) (SWC-Karnataka Round up would be the post name)

ReplyDeleteI wish not acquiesce in on it. I think nice post. Particularly the appellation attracted me to study the intact story.

ReplyDelete