It’s been a busy winter for film

retrospectives of Indian Film Directors of yore.

Not long after Liberty screened a week long retrospective of

Shyam Benegal’s classics in December 2015, Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan followed up with

a retrospective of Bimal Roy’s films that ran between Jan 11-16, 2016.

Organised by Bimal Roy MemorialCommittee (BRMC) in collaboration with Cine Society, the retrospective was held

to commemorate the 50th death anniversary of the legendary

filmmaker.

Ashutosh Gowarikar and Shabana

Azmi inaugurated the retrospective. It ended yesterday with the screening of Bandini (1963), finding little or next

to nothing coverage in the mainstream press or online!

Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan’s

Auditorium or Bhavan’s Auditorium as it is commonly known is a relative unknown

as a hub of cultural events compared to other, better known, venues in this

part of Bombay .

The auditorium is within walking

distance from Wilson

College

Before the television boom

sidelined the primacy of Doordarshan (DD) as the television channel of choice

(or compulsion as many would remember it) that stretched well into the 1980s,

DD would serve up classics via film retrospectives of its own from time to time.

It was a time before the advent

of CDs and when VCRs were not easily affordable to most.

So the venue was your drawing

room, and screen space, a small TV occupying a pride of place in the scheme of

the room where visitors were entertained.

The scale of a large screen and

the community of film goers seated around you were missing, but the import of

films that straddled the parallel cinema movement struck a chord among film

lovers and those who were on the way to joining them in their love for films.

To the generation from before,

the screenings on DD brought nostalgia, renewing sentiments of their origins in

the hinterland. To the new generation, the films introduced them to the older

generation and the mores from where they came from, and as a consequence, to an

India

somewhat removed from the realities of drawing rooms in towns evolving toward a

homogeneity we see now.

That’s how I first saw Bimal

Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen in addition to

Ritwik Ghatak’s oeuvre, Ray’s classics and a host of others.

The Bimal Roy Retrospective

opened early this week with Do Bigha Zameen, his signature film.

While we hoped to watch them this

week, work and other commitments meant we did not find our way to the venue

until the fag end of the retrospective, the day they were screening his Parakh.

~

We returned from Chowpatty beach

as the Sun began to dip and the first lights came on across the street from the

beach in Girgaon.

Traffic streamed both ways on the

sea-facing road named after Netaji Subash Chandra Bose – toward Walkeshwar on

my left and SOBO on the right. The temperature had dropped by a notch.

Policemen gathered on the pavement watching traffic halt on signal turning red.

Café Ideal lay directly across

the road while Sukh Sagar Veg Restaurant lay at a diagonal, along the road (Sardar Vallabbhai Patel Road )

that branches off the sea facing road we had just crossed, and runs through

Khetwadi, Dongri and beyond, ending on P.D. Mello Road that runs along Mumbai

Port Trust docks. Beyond that is the sea, again.

With the Eastern Freeway

operational, P.D. Mello road has shed its quiet for traffic streaming along the

freeway, a route of choice for commuters travelling to the faraway suburbs of Vikhroli,

Kanjur Marg, Bhandup and Mulund, and beyond.

~

I was keen on a bite at Sukh

Sagar so we crossed the road and found ourselves a seat in the restaurant.

After tucking in a spread of Bombay Pav Bhaji, Vegetable Grilled Sandwich and Nescafe (they don’t

serve tea) we stepped out and took the turn that led us down Hughes Road , past the Mercedes Benz

showroom. Traffic was light on Hughes

Road .

Soon, streamers of glowing light

bulbs descending from a building at the corner of K.M. Munshi and Pandit

Ramabai Roads announced Bhavan’s Auditorium. The decorations were part of Bimal

Roy Retrospective underway at the venue.

A standee placed outside and

visible to everyone on the street listed the films scheduled for the duration

of the retrospective. Each screening got underway at half past six in the

evening.

Up a short flight of steps led

past a table at the entrance stacked with copies of Bimal Roy’s biography.

We had landed at the venue half

hour after Parakh commenced so we

meandered in the hallway looking at displays put up, including those supporting

the event, Zee Classic and CMC among others.

Each day, the poster of the film

scheduled for screening is put up by the entrance to the auditorium.

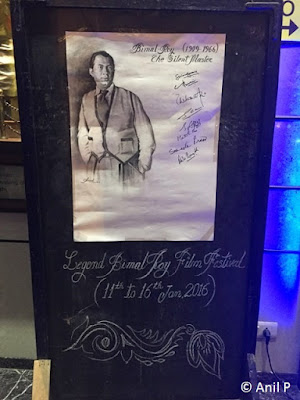

On a stand-up board, a sketch of

Bimal Roy was accompanied by signatures of Bollywood Dignitaries acknowledging

their presence at the retrospective.

“Asha Parekh was present at the

start of today’s screening,” a man manning a temporary stall of DVDs of Bimal

Roy films set up on a table told us as we lingered by the sketch. Sure enough she had signed in her presence at the bottom.

Apparently, each day of the

retrospective was graced by Bollywood figures associated with Bimal Roy.

I find the designs of posters of

yesterday year films charming. They’re uncluttered, expressive without being

angst ridden, and project an innocence of a time long past.

Ranged on the table for sale were

a mix of films he produced and directed and those he produced.

Of the films he directed, the

following were on display – Do Bigha

Zamin (1953), Devdas (1955), Sujata (1959), Parakh (1960), and Prem Patra

(1962), each priced at 120/-.

Of the films he produced but were

directed by others, the following were on display – Apradhi

Kaun? (1957), Parivar (1956), Madhumati (1958), Kabuliwala (1961), Usne Kaha

Tha (1960), priced 120/- each.

Also on sale were collections of these

titles at different price points.

To those who came of age in the

era of his films, the titles on sale would guarantee a trip down the memory

lane, reminding of events in their own lives where woven with these films.

We stepped into the hall. The

screen flickered with a scene from Parakh. Much of the hall was full and where

seats were vacant, toward the back, viewers were boxed tight at the entrance to

the rows and unwilling to make space to let latecomers pass.

A cursory look at the audience

seemed to suggest that most of them belonged to the generation familiar with

the mores of the time Bimal Roy’s films were set in, or at the very least they likely

grew up seeing his films.

We stepped out of the screening and

made for the DVDs, purchasing Parivar

and Benazir.

Benazir because K felt a love story set in Lucknow would make for interesting viewing.

And, Parivar because I felt it’d be interesting to see how a story of a

joint family of five brothers and their families “living and sharing each others’ joys and sorrows” would pan out

after “an argument breaks out over a

glass of milk, and the entire family is thrown into chaos, and the only resolution seems to be nothing but dividing the entire property amongst the brothers and their respective families.”

We stepped out into the night,

passing a compound home to a cottage standing all by itself, a rare but welcome

sight in a city overrun by buildings.

Up ahead we stepped into Westside

where K made a quick purchase before we set off toward Gamdevi, settling for

dinner at By The Way: The Parsi Kitchen.

That was an experience in itself, a story for another time.