A snake lay flattened on the

road. Using a stick I found in the brush roadside I turned it over to see if I

could identify it. I couldn’t. It was flattened to its skin, scattering scales around, making identification ever more difficult more so since I’m no expert on

snakes.

Ahead, the Ring Road sloped and

ran straight before curving out of sight; later in the day we would ride it on

our way to Torvi, past Navraspur. Trucks droned up the incline, shattering the

silence in the countryside that’s gradually losing its quiet and open expanse

to an expanding population radiating outward of the city centre – Bijapur.

I stepped past the twisted figure,

a sign of a last act of desperation as it drew its body close upon suffering

the first impact before suffering another, and another. Time came at it like a sledgehammer practicing its blows. In its death it had frozen its

attempt at clinging on to life.

Crunching gravel we walked to

remnants of an old stone structure a little distance away, an imposing stone gate

that stood all by itself.

To the left of the gate a crumbling edifice stood unsteadily, likely a remnant of a wall that extended from the gate. Very little remains of it to help identify its function positively. The structure of the gate itself has survived well with the exception of battlements surmounting its roof.

I wonder if the rooftop battlements, of which only a hint now remains in the surviving embrasure to one corner of the roof, were merely decorative elements or formed a part of an active defensive line extending along walls from the gate, guarding its approach. Grass spouts through the lone crenel, obscuring it to all but a persistent eye. I notice a crumbling fortification at the same rooftop corner as the surviving battlement. A turret? A resting place? A control room? I cannot tell for sure.

Wildflowers grew among thorny bushes, relieving the stark landscape that stretched flat northward. The great plains of the Deccan stretch a long way. Winds play in the open expanse, winds so strong they'll knock the unwary off their footing.

Bijapur is a city of monuments,

in ruins or otherwise, together stringing a history under Muslim rule that was

both bloody and uplifting. The city itself traces its pre-Islamic history to

the reign of the Hindu Chalukyas, the Yadavas, and the Sangamas of Vijayanagara

before Islamic invaders took the sword to them.

The old, arched stone gate rose

high over me. I walked through it not knowing if I was entering the gate or

exiting it as I made for a mound past it, but most likely exiting it. From the mound I hoped to get a

better view of the Bijapur countryside that lay not far from my cycling route from

years ago. A masjid, visible through the gate, stood on rocky ground a little distance away.

Madhav and I were on our way to

Navraspur, and beyond, to the temple at Torvi, a permanent fixture on my

periodic visits to this part of Karnataka, a ride I hoped would relive memories

from long, long ago for, finding myself in Bijapur during vacations from school

I would mount VRN’s bicycle and head out on the NH 12, better known as Athani

Road, for Torvi over six kms. away.

VRN has since passed on to the

great beyond, and the city I first experienced as a toddler clinging on to his

cycle’s handlebars, legs crossed under me as I tagged along with him around the

city, one that I can no longer imagine without its association with VRN survives

to tell its tales in the many monuments in disrepair within its fort walls and

outside, the latter in the general direction of Navraspur, structures that were

at one time likely a part of a grand design Ibrahim Adil Shah II sought to

construct at Torvi after removing his seat of governance in 1604 from the

citadel in the old city to new fortifications underway around Navraspur and

Torvi. Among others they included palaces, and water tanks that were as much architectural

marvels as they were lifelines supplying Bijapur, and the ill fated new city, with water.

Only the new plan never saw

fruition, the new seat of governance near Torvi was razed to the ground and

plundered by Malik Ambar in 1621 A.D. Abandoned, the seat of governance

returned to Bijapur’s old citadel never to leave it again. Ibrahim Adil Shah II

died soon after.

~

It is September; the sparse rains

that come Bijapur’s way in the north of Karnataka have given way to clouds

marching in the sky, turning the light a heavy shade of gray, and the

atmosphere, sombre.

Rather than continue to Navraspur

and Torvi on Athani Road (NH 12) straight west that goes on to Belgaum via

Athani, Madhav and I turned off it, onto Solapur Road after taking a right soon

after the road breaches the Adil Shahi era fort near the bastion named

Sherza-i-Buruj (Lion Tower) where the medieval monster of a canon, the 55 ton

Malik-e-Maidan (Lord of the Plains),

sits in splendid isolation, pointing West at the horizon from whence Bijapur’s

enemies once threatened it.

The canon, a star attraction with

locals and visitors alike, was a war trophy carted back to Bijapur by Ali Adil

Shah after vanquishing Nizam Shah in 1562. At over 4 and ½ metres, the Malik-e-Maidan is

said to be the largest battlefield bell metal armament ever cast in its time by

Muhammad Bin Husain Rumi in 1549 AD in Ahmednagar as noted by an inscription on

the canon.

If not for the railing fencing

off the viewing enclosure I’ve little doubt that inquisitive visitors would

attempt to slide down its barrel, comfortably fitting into the opening 1 and ½

metres wide.

Its sheer bulk weighing in at a

staggering 55 tons is said to be the key reason why the British did not steal

it out of India

as booty given the cost of transporting it to the coast after first considering

sending it to the King of England in 1823. It was just too big a loot to carry,

else like with other loot gracing British Museums, the Malik-e-Maidan would’ve

likely occupied a corner in a far removed from the landscape.

Leaving Athani Road (NH 12) after taking a right turn, we rode along Solapur Road before

turning off it, onto Jatt Road,

riding past Darga Jail, Khwaja Ameenuddin Chisti’s Dargah, and Phani

Parshwanath Jain temple, eventually joining the Ring Road near where the snake

lay flattened.

The Ring Road circles back to Athani Road shortly

before Navraspur; Torvi lies a short distance further on. Over the years, I’ve

ridden both, the Athani Road

and Solapur Road

out of Bijapur on my way to Belgaum,

and occasionally Solapur. In daytime, early morning to be precise, the Deccan landscape makes for a pleasing ride.

The customary ride to Torvi is as

much a homage of sorts to the rite of passage that cycling from the city centre

to the then sleepy village six kms away once was as it is a tradition for, the

Narasimha temple built underground and to reach which one has to navigate a

short dark passage chanting “Hadhey, Hadhey” is of particular significance to

my family, and hence to me. My mother would never fail to remind me to chant

“Hadhey, Hadhey” (make way, make way) as we negotiated the underground passage

that leads to the sanctum sanctorum.

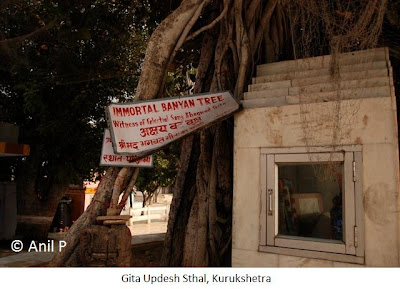

On my way to Torvi astride VRN’s

bicycle, the Atlas type, I would pause on rutted roads that ran past views

similar to that in the picture above, wondering about them.

There was little or nothing to

identify their origins except they were a permanent fixture in the landscape

from as long back as anyone could remember, atleast among those I ventured out

with, Jai among others. The mullahs with their thick black beards extending at

an angle from large jaws set off by piercing black eyes were a tad intimidating

at any rate and as a kid I knew better than to tangle with their lot, helped no

doubt by several intimidating experiences in the community they served and

lived.

I wondered after the purpose of

the gate towering before me. Madhav meandered around it. Two women sat in front

of a disused masjid on a mild elevation a little distance away, muslim women

tending goats foraging in the brush around.

On a subsequent visit a year later,

again with Madhav, passing cowherds would identify the masjid for me as

Dharyali masjid.

“It’s no longer used now,” one of them would say in a sing song Kannada dialect peculiar to Muslims from North

Karnataka.

The same man, pointing his stick to the apparently mysterious gate I now beheld would identify it

as Pani Darwaza (Water Gate). “In those days water would flow through it from

there,” he said, showing me the path the water took before pointing through the gate, past the Dharyali masjid, to the

open expanse behind, indicating the direction from which the water flowed. Further exploration in the direction he pointed out reveals what appears to be remnants of a masonry construction, probably belonging to the reservoir. Again, I cannot be sure if the reservoir brought its retaining walls this close to this gate. A large reservoir once existed at Torvi, of that I'm certain. Maybe it still does.

The gate could not possibly have been built as a conduit for water. As an approach to the reservoir, likely, but surely not as a water channel. It had to be a part of fortifications if not an embellishment.

There was little to indicate with any clarity except possibly to those who’ve lived there and heard stories passed on from generation to generation.

Behind us, in the general direction

from where we came, in a similarly ancient patch of the countryside, a massive stone

structure lies in disrepair, figuring in some significant way with water works

the Adil Shahi kings effected to supply Bijapur city with water drawn from the

reservoir located near Torvi over six kms. away.

On another visit many, many years

ago, I had made my way to the abandoned structure, marvelling at its scale and

architecture, wandering through it while wondering not so much as to its

function of which I was aware but about how it must’ve functioned in its day, and

the thought behind its architecture. I wonder still.

In time the Adil Shahi reign came

to be known for innovative engineering to put in place secure water pipelines

to supply the city, including underground water channels carved in rock and

interspersed with chambers and inspection holes, control towers, water

cisterns, wells, ponds, and the many water tanks that dot the city, most

notably the Taj Bawdi and Chand Bawdi, each an exercise in lending regal

splendour to their purpose, a place to bathe and draw water from, a space to seek

respite from the sun.

Apparently little has changed in

the patch of landscape we had stopped by to wander about. The gate’s arch

frames a masjid behind.

No wall led from the gate. There

was nothing to indicate where the gate led in the days gone by except for

overgrown thickets crowding tombs and a mosque where men in skull caps sat

chatting in a corner.

From the mound we ascended for a

better view of the countryside, two more structures revealed themselves a

little over fifty yards from the arched gate and Dharyali masjid. One appeared

to be a mosque with two minarets, the other, most likely a tomb, or maybe both were tombs though I cannot recollect seeing one with minarets.

Zooming in I could see men in

skull caps gathered to one corner of the platform that conveyed a passage around

the main chamber walled off on the side facing us.

Two Muslim women emerge from the thickets along a dirt path

winding between thorny bushes, past the dilapidated monuments I now viewed

through my lens.

For a fair distance to the north, nothing moves.

Slowly the landscape converges to a canvas, securing the feelings it invokes,

into colours turned sombre from the weight of history and ignominy heaped by an

uncaring present.

Except for a wooden triangle with

notches I find lying centered on the approach to the arched gate that Madhav

said was most likely an implement used in performing Black Magic, one that he

forbade me from picking up, there was little sign of life about the place

except for a black goat grazing in the thorny shrubs.

It might have as likely been an

instrument used in accompanying the dead to their burial places. I cannot be

sure except, on my subsequent visit to the same place close to a year later,

Madhav and I found two sets of stones heaped on the approach to the arched

stone gate in the manner of burial mounds, and were more likely than not graves of fairly recent origin. Graves at the gate? Whose? Why here?

Bijapur has always posed me more questions than answers, retaining its mystique and mystery in unanswered queries.

Walking back from the arched gate, we continue along the Ring Road

and circle back to Athani Road

(NH 12) before continuing to Torvi, past Navraspur.

I will tell of Torvi another

time.