I never attempted to bicycle to Tambdi Surla ever again. Once was enough.

I never attempted to bicycle to Tambdi Surla ever again. Once was enough.And moreover the road to Tambdi Surla through Sacorda where it turns left off the national highway 4A that runs on to Mollem on its way through the Anmod ghats to Belgaum in Karnataka, demands of the cyclist a strong heart to negotiate the undulating terrain in the heat of a Goan summer. It took me a long time to pedal to Tambdi Surla that summer day many years ago. However, halfway through the journey after I had pedaled about twenty kilometres, I propped my bicycle against a mud-house in a village along the way, smiled at the owner who’d come around to see what the commotion was about, and hitched a ride on a two-wheeler to the temple. To my luck, the rider was headed to Tambdi Surla the village where the temple is located. Before I got off his scooter, he assured me that if I waited long enough at the turn in the road near the village I’m bound to find someone who would offer me a ride back the way I’d pedaled. “Then you can get off where you’ve parked your bicycle and cycle back home,” he said. Then he asked me why I had chosen to bicycle such a long distance – twenty kilometres in the middle of a Goan summer is a very long distance. I was drenched from sweat, and was wary of pausing for breath lest my legs cramp up. “I enjoy bicycling in the countryside, and thought the route to Tambdi Surla might be a challenge,” I replied.

The bicycle offered me an escape from the textbooks. That morning I started early, and stopped on the way at Khandepar for pao-bhaji at a local inn opposite the road to Opa that runs past the ancient Saptakoteshwar temple by the banks of the Khandepar River before culminating at Opa water works, the source of water for much of Goa. Years later, Ajay and I frequented the inn for mirchi-bujjiyas until the cook lost it quite inexplicably. The color of mirchi-bujjiyas turned to a consistent burnt red from the rich blend of pale yellow with a warm brown to it that we so enjoyed eating even as our mouths caught fire and eyes watered from ingesting the extra spicy green chillies cooked in besan. Later that year when my school closed for the vacations, I would return to Khandepar where I helped with paperwork at the tractor yard, getting them registered at Margao. I had a good time the three months that I cycled the six kilometers to Khandepar each day and back the same way. And, the days when there were no new tractor arrivals, I got back on the bicycle and pedaled further up, along the way to Bondla with the wind in my teeth. Those blue skies above me were irresistible.

After downing the pao-bhaji, I mounted the bicycle in the direction of Mollem, and just before the bridge over the river I pedaled past a narrow road to my left that goes up an incline before skirting a playground where a fig tree fruits in the summer and down a rocky slope where three caves cut in laterite face a fourth one in silence. They rest in the side of a gentle hill after they were excavated decades ago. Legend has it that Pandavas built it during their exile as they traversed the country. If it is true then their origin is set back by thousands of years. However, I’m perplexed by the sheer number of such caves around the country whose origins are attributed to the Pandavas.

When Jagdish and I visited the caves last April, A explored the narrow pathway cut in the banks of the Khandepar river that flows from under the bridge a short distance away, and sweeping past the bend that hid the bridge from us. Now, when I occasionally stop by the caves, I walk down the narrow pathway where it disappears beneath the river surface, and sit on the edge with my legs in the water. Invariably I spot a Kingfisher diving for fish from an overhanging branch. Usually I spot the White Breasted Kingfisher doing the honors; sometimes it is the Small Blue Kingfisher. I never tire of watching Kingfishers skimming the surface of the river at full tilt before taking up position on another of the many overhanging branches of trees that line the banks. Occasionally I spot a narrow dugout anchored to the bank with nylon ropes. If the water is clear, and chances are the water is clear in the summer, fishes are visible beneath the surface; sleek, black creatures.

Clumps of bamboo in front of the caves line the banks of the river. In spring time, Magpie Robins seek the upper reaches of the bamboo and let their melodies float in the breeze. Then the bulbuls join in and quicken the pace, letting out their own chorus. I used to try and separate the conflicting melodies in my mind but soon gave up. After a time, it really does not matter, they invariably mesh well together. Also, it was here that I saw a Tree Pie for the first time as it flew past me and into a tree to my right. Jasmine fragrances from plants that circle the caves trail me in the spring when I ride down to the laterite caves. I’ve rarely seen people visit the caves and it suits me just fine.

As I pedaled on the road in the direction of Mollem, a gentle breeze stirred in the mango trees along the route. Gulmohars were in bloom. Occasionally an Indian Laburnum (Amaltas) burst forth in golden melody in the brown hills. As I scoured the countryside for these bursts of colour, reveling in their enthusiasm, I remember thinking that I could not have been happier that summer. Ahead, a man in loin cloth herded his buffaloes to the side of the road near Usgao to make way for a Karnataka State Transport (KSRTC) bus on its way to Belgaum. It had left Panjim an hour and half ago, covering forty kilometers through the countryside. Belgaum lay 115 kilometres ahead. I slowed down behind the herd of nervous buffaloes before passing them in the cloud of red colored dust swirling in the wake of the bus where it had swerved off the road to make way for a mining truck hurtling from the opposite direction. Then more mining trucks passed us on the rutted road.

After I got off the scooter and thanked the scooterist for the ride, I walked the final stretch to the stone temple at Tambdi Surla, passing silent trees, and dodging the shadows they threw on the even quieter road. Traveling to Tambdi Surla, known to be home to the ‘only known specimen’ of Kadamba-Yadava architecture in basalt available in Goa, is a pilgrimage I’ve undertaken several times over the years. The fact that it nestles in the mountains, far away from tourist-traffic, often overwhelming, that other temples in Goa are witness to, starting with the end of monsoons in Oct-Nov, and petering off as Carnival comes around on the eve of the season of Lent when Christians fast and offer penance, makes it an attractive travel destination in my scheme of things. In two months time after the Carnival the first monsoon clouds wind their way across the Arabian Sea for their rendezvous with the Western Ghats. And I imagine the stone temple at Tambdi Surla, nestling in the Western Ghats mountain ranges, is among the first to welcome the monsoons to Goa.

After I got off the scooter and thanked the scooterist for the ride, I walked the final stretch to the stone temple at Tambdi Surla, passing silent trees, and dodging the shadows they threw on the even quieter road. Traveling to Tambdi Surla, known to be home to the ‘only known specimen’ of Kadamba-Yadava architecture in basalt available in Goa, is a pilgrimage I’ve undertaken several times over the years. The fact that it nestles in the mountains, far away from tourist-traffic, often overwhelming, that other temples in Goa are witness to, starting with the end of monsoons in Oct-Nov, and petering off as Carnival comes around on the eve of the season of Lent when Christians fast and offer penance, makes it an attractive travel destination in my scheme of things. In two months time after the Carnival the first monsoon clouds wind their way across the Arabian Sea for their rendezvous with the Western Ghats. And I imagine the stone temple at Tambdi Surla, nestling in the Western Ghats mountain ranges, is among the first to welcome the monsoons to Goa. The temple is situated in the Bhagwan Mahavir wildlife sanctuary. I particularly remember one trip when I was showing Jai around the place when he jumped up in alarm at seeing a Green Whip snake crossing his path. I set off in pursuit as it dodged stones and plants until I cornered it by blocking it path. Promptly it climbed up a small plant, curving up in classic Whip snake pose. As I moved cautiously in a semi circle, covering its exit, it swayed gently, as if undecided on its future course of action. It was a beautiful specimen; setting off its fluorescent green against the brown of the earth. I took pictures, framing it on the green plant. Then it left. However, photographing the Skink proved to be more difficult.

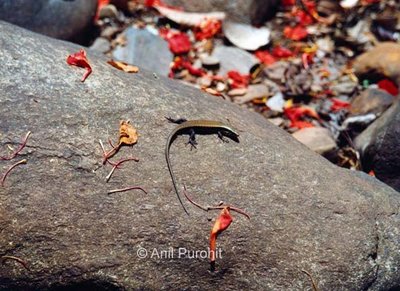

The temple is situated in the Bhagwan Mahavir wildlife sanctuary. I particularly remember one trip when I was showing Jai around the place when he jumped up in alarm at seeing a Green Whip snake crossing his path. I set off in pursuit as it dodged stones and plants until I cornered it by blocking it path. Promptly it climbed up a small plant, curving up in classic Whip snake pose. As I moved cautiously in a semi circle, covering its exit, it swayed gently, as if undecided on its future course of action. It was a beautiful specimen; setting off its fluorescent green against the brown of the earth. I took pictures, framing it on the green plant. Then it left. However, photographing the Skink proved to be more difficult.A flight of steps opposite the entrance to the temple leads to a stream below. It runs hundred-odd metres in the direction I had come before meeting a bigger stream where the road bringing visitors to the temple ends. For years, under a tree where the road draw up short, a flower seller had set up shop, selling coconuts, incense sticks, and flowers to devotees who offered them to Lord Shiva in the temple. My regular trips to the temple had induced a familiarity between us. “Visit Tambdi Surli during Mahashivratri,” he told me once. “It is quite a sight at the temple.” I nodded, and resolved to do so. Somehow I haven’t made it to Tambdi Surla during Mahashivratri. Now he is no longer the only flower seller there.

Where the road comes to an abrupt end not far from the tree, visitors cross a small bridge to get to the temple. From here, the temple unveils itself between branches of trees that crowd the cobbled path leading to the temple. In the spring of 2001, I took the flight of steps down to the dry stream bed in search of a Laughing Thrush whose call I had heard while exploring the length of the temple plot adjoining the stream. Instead, on rounded stones set off by brightly colored Gulmohar flowers blown free from Gulmohar trees on the banks of the stream, I saw several Skinks quick-stepping across the stones that littered the stream bed. It was awhile before I finally managed to take a picture of one skink basking on a stone amidst petals of Gulmohar flowers. By then I was sweating from chasing them only to find them disappear under the stones just when it appeared that I might pull off a good photograph.

Where the road comes to an abrupt end not far from the tree, visitors cross a small bridge to get to the temple. From here, the temple unveils itself between branches of trees that crowd the cobbled path leading to the temple. In the spring of 2001, I took the flight of steps down to the dry stream bed in search of a Laughing Thrush whose call I had heard while exploring the length of the temple plot adjoining the stream. Instead, on rounded stones set off by brightly colored Gulmohar flowers blown free from Gulmohar trees on the banks of the stream, I saw several Skinks quick-stepping across the stones that littered the stream bed. It was awhile before I finally managed to take a picture of one skink basking on a stone amidst petals of Gulmohar flowers. By then I was sweating from chasing them only to find them disappear under the stones just when it appeared that I might pull off a good photograph. Butterflies are aplenty in the wildlife sanctuary, and so are various lizard species. I particularly remember seeing a mass migration of Common Crow (a butterfly species) near Caranzol in early 2002, not far from the entrance to the wildlife sanctuary in Mollem. Philip and I had paused on seeing the sight unfold before us, dodging them lest we trample any. They must have numbered over six hundred. Three hours later when Philip and I returned by the same path there was no trace of them. On another sojourn to the temple, I managed to photograph a Common Crow as it rested under a leaf in a thicket by the temple. I suspect it was laying eggs though I couldn’t be sure in the gathering dusk. By then, Jagdish and I had spent the last daylight moments clicking a Forest Calotes on a plant near where we had gone to relieve ourselves. Talk of unlikely opportunities!

Butterflies are aplenty in the wildlife sanctuary, and so are various lizard species. I particularly remember seeing a mass migration of Common Crow (a butterfly species) near Caranzol in early 2002, not far from the entrance to the wildlife sanctuary in Mollem. Philip and I had paused on seeing the sight unfold before us, dodging them lest we trample any. They must have numbered over six hundred. Three hours later when Philip and I returned by the same path there was no trace of them. On another sojourn to the temple, I managed to photograph a Common Crow as it rested under a leaf in a thicket by the temple. I suspect it was laying eggs though I couldn’t be sure in the gathering dusk. By then, Jagdish and I had spent the last daylight moments clicking a Forest Calotes on a plant near where we had gone to relieve ourselves. Talk of unlikely opportunities! Later, as Jagdish and I sat on a large rock in silence watching several insects enact a riveting drama in a pool of water stagnating in a depression in the rock, I took my eyes off a frog that had disturbed a Stick insect in the pool to look at a Dragon fly that had landed on a bamboo shoot overhanging the small pool. Behind the Dragon fly, dusk had fallen, silhouetting it against the faint blue of the sky. An occasional noise in the jungle alerted us to life beyond the stillness where we sat on the rock, covered on all sides by vegetation, but from where we sat those noises took shape only in our imagination. Jagdish sat leaning on his hands stretched out behind him. His Pentax K1000 rested by his side. After several hours walking in the vicinity of the temple, looking for butterflies and birds we could photograph, he was relishing the drama being played out in the stagnating pool in front of us. Without getting up on my feet, I dragged myself forward, cautious not to startle the dragonfly and took a photograph.

Later, as Jagdish and I sat on a large rock in silence watching several insects enact a riveting drama in a pool of water stagnating in a depression in the rock, I took my eyes off a frog that had disturbed a Stick insect in the pool to look at a Dragon fly that had landed on a bamboo shoot overhanging the small pool. Behind the Dragon fly, dusk had fallen, silhouetting it against the faint blue of the sky. An occasional noise in the jungle alerted us to life beyond the stillness where we sat on the rock, covered on all sides by vegetation, but from where we sat those noises took shape only in our imagination. Jagdish sat leaning on his hands stretched out behind him. His Pentax K1000 rested by his side. After several hours walking in the vicinity of the temple, looking for butterflies and birds we could photograph, he was relishing the drama being played out in the stagnating pool in front of us. Without getting up on my feet, I dragged myself forward, cautious not to startle the dragonfly and took a photograph.  As the shutter came down in a booming click, heightened by the silence, the Dragon fly took off.

As the shutter came down in a booming click, heightened by the silence, the Dragon fly took off.