And, each time I pass the Victoria lamp on the wall behind the door where the stairs wind their way up, passing among other artifacts statues of Hindu deities, and a steering wheel of a ship, I cannot help but wonder about the horse that drew the Victoria carriage along quiet roads in the light of the lamp. Sometime ago the lamp cracked, and a thin line now snakes along its length. But the glow of the bulb it houses is undiminished, like the spirit of the man who put it up there. Percival Noronha turned 83 last month.

And, each time I pass the Victoria lamp on the wall behind the door where the stairs wind their way up, passing among other artifacts statues of Hindu deities, and a steering wheel of a ship, I cannot help but wonder about the horse that drew the Victoria carriage along quiet roads in the light of the lamp. Sometime ago the lamp cracked, and a thin line now snakes along its length. But the glow of the bulb it houses is undiminished, like the spirit of the man who put it up there. Percival Noronha turned 83 last month. The landing, covered by red carpet and lit up by light from the window that Percival Noronha uses to peer out to check on visitors ringing his door bell in the street below, opens into a sitting room. A brass-lamp stands in the corner by the door, and another hangs from the wall above it. Inside the room, intricately carved furniture wear their Portuguese influence in the same easy manner that Fontainhas, Goa’s Latin Quarter, wears its Portuguese identity in the heart of Panjim, its Indian context inextricable from its Portuguese past. Then, as always, after looking around the room I rest my eyes on the black and white pictures of his parents framed on the wall.

The landing, covered by red carpet and lit up by light from the window that Percival Noronha uses to peer out to check on visitors ringing his door bell in the street below, opens into a sitting room. A brass-lamp stands in the corner by the door, and another hangs from the wall above it. Inside the room, intricately carved furniture wear their Portuguese influence in the same easy manner that Fontainhas, Goa’s Latin Quarter, wears its Portuguese identity in the heart of Panjim, its Indian context inextricable from its Portuguese past. Then, as always, after looking around the room I rest my eyes on the black and white pictures of his parents framed on the wall.I let my eyes drop to the glow from the two lamps under the framed photographs as it reaches up, and crawls across the wall, casting memories in the shade of the wall, green. Monsoons got through the coat of paint, and green paint flakes in a corner by the window flanking the photographs. ‘Not everything green is coloured green’, I remember thinking while A looked around the room, running her eyes over the mantle pieces and wall pieces that Percival Noronha picked up over the years on his travels across the world, lecturing on Goan heritage and architecture in universities overseas. He had excused himself to answer the phone in the adjoining room where, under a framed map of Goa rendered in a Portolan style reminiscent of maps that sailors centuries ago used in navigating the seas by compass bearings, a vintage telephone receiver rests regally in a matching rest. I hear him talking to someone on the phone. His voice rings out from the room in clear tones. I find this tonal quality of voice unique to old Goan houses, particularly those home to Goan Christian families.

Seeing the map again later that day reminded me of the first time I saw it on my visit to his house in 1998. We were in the middle of a conversation about the quality of workmanship in the years gone by when Percival got up from his chair and said, "Come, I'll show you what I mean by quality of craftsmanship." I followed him into the adjoining room where he keeps the telephone. There, he pointed to the map on the wall and said, "This is Budkuley's creation. Budkuley was a master draughtsman, the best I ever saw. He did all this by hand." I watched him stand there, his hands folded behind his back, admiring the map. It was brilliantly crafted.

"Budkuley was thin, his wrists barely the size of two fingers put together," Percival said. "The last time I saw him was eight years ago. He was ill, down with fever and barely able to get up." Percival got him medical help and he got better.

We wait in the hall while he answers the phone in the other room. I picture him standing by the window overlooking the narrow street, the map facing him. Eventually, I turn my face up to look at the picture of his mother, Aurora Vital e Noronha (1896-1980). She was from S. Matias in Mallar (Divar), an island near Panjim that I last visited with A. K. Sahay three years ago, and where Percival Noronha once found a piece of meterorite years ago as it crashed down near where he stood in the countryside. He showed it to me sometime back. I doubt if he remembers where it is now. It must have passed hands, and ‘disappeared’. His mother has a kindly face. Light from the verandah to the back of the house streams in through the open door where his cat sits watching us, and reflects candle-like off the spot where her collar bones meet. I hear his cat purr. Not too long ago, the cat knocked a large vase off its rest, breaking it. Later in the evening as we prepared to take leave of him I asked him the name of the cat. He smiled and said, "One of the students named the kitten Priti taking it to be a female. As the cat grew up I realised it was a male, so I changed its name to Pritam."

Standing there and looking around, it’s like nothing has changed in the years since I first met him when I was in college, starting out in life. I’m still starting out. Percival Noronha has grown older, and so have I. Once in a while I go to Fontainhas to visit him, and we spend time talking. And each time, I leave his place amazed at the energy and enthusiasm he brings to bear in our conversations.

His father, Antonio Jose de Noronha (1884-1962) came from Loutolim, a sleepy village near Borim where Mario Miranda, the legendary Goan cartoonist, has his home. Antonio Jose left Goa for Uganda in search of work, bringing up young Percival in the African country. In 1929, the year Percival Noronha turned seven, the family returned to Goa, and Percival went to Lyceum to complete his schooling. That he did not is another story, and it probably helped him be his own person. In 1961, India reclaimed Goa from the Portuguese. At the time Percival Noronha was the Chief Information Officer and reported to the last Portuguese Governor General of Goa, Vassalo da Silva, a man Percival describes as 'efficient, and very energetic'. Talking of his time working in the Portuguese administration, he said, "Each Saturday morning, I accompanied the Portuguese Governor General to Daman by plane."

"The Governor General used to check on the progress of development projects, and attend to routine administrative work before traveling to Diu to check on the same. Sometimes, we flew to Diu directly before traveling to Daman. In the evening we returned to Goa," Percival said. Goa, Daman and Diu, along with Dadra and Nagar Haveli were part of Portuguese India for over 460 years. After India drove the Portuguese out in 1961, Goa, Daman and Diu were administered as a single union territory before Goa was granted statehood in 1987.

Percival's house dates back a long way as do most houses in Fontainhas. Its façade is painted deep red, the colour of red oxide. “When I was renovating it in 1987, I found a corroded beam that was marked 1884. I asked the carpenter to cut out the dated portion of the beam and save it. The rest, I asked him to dispose off,” he told me recently over the phone, his voice betraying disappointment as he continued, “and that carpenter, dunno what he did, disposed off the whole lot.” His voice trailed off. In the other room I hear him return the receiver to the telephone stand. Footsteps sound in the room behind the wall as he walks in through the door, hair askew on his head from the breeze blowing in through the door that opens into a balcony. He pats the few strands down and smiles. He leads us through the door to the dining room that functions as his study. Piles of books and papers are scattered across the large wooden table. Its legs end in finely carved lions. I pull a chair back and sit down, taking care not to place my feet near the lions.

In the other room I hear him return the receiver to the telephone stand. Footsteps sound in the room behind the wall as he walks in through the door, hair askew on his head from the breeze blowing in through the door that opens into a balcony. He pats the few strands down and smiles. He leads us through the door to the dining room that functions as his study. Piles of books and papers are scattered across the large wooden table. Its legs end in finely carved lions. I pull a chair back and sit down, taking care not to place my feet near the lions.

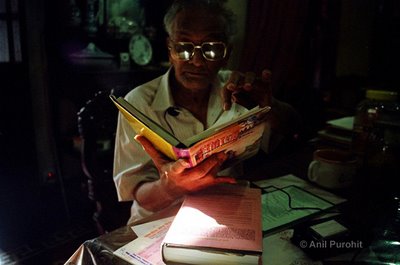

Light streams in through the balcony in the corridor behind us and bounces off a book on the table before glinting in his spectacles, lighting up the book in his hand. It is late afternoon in Fontainhas. His fingers turn the pages in the book where his paper titled Old Goa in the context of Indian Heritage is published in the anthology Goa and Portugal: Their Cultural Links. He presented the paper at the International Symposium on Inter-cultural Relations: Portugal and Goa organized by the University of Cologne in 1996. The book is a collection of 21 papers presented by scholars attending the symposium. Silence settles in the room. I catch sight of the cat siddling to its food bowl in the verandah. As I sit there waiting for him to turn to the page, I take in the smell of wood, books, and life, and it feels good. It's been a long time.

"Ah, here it is,” he says, his eyes lighting up as he holds the book, Goa and Portugal: Their Cultural Links, out to me. I bend forward to read the title on the page: Old Goa in the context of Indian Heritage. Behind me, another cat joins the first one at the food bowl, and the first cat, Pritam, is not amused.