It was as much of a surprise as it was a chance meeting with Jairam Mohite this February that set a sultry afternoon in Yeoor to the tunes of an old Mandolin, and even older memories. M Satish and I had ridden to Yeoor hills for a bite of lunch, and a bit of stillness. We got them both, and a slice of melody too.

Earlier in the day, as we took the turn opposite Upwan lake up the hill toward Yeoor in Thane (west), adjoining Mumbai, we passed under an arch welcoming travelers to the hills, favoured for trekking by trekkers looking for short treks. It was February, the time when heat begins to inch across the city, prompting people to seek out cooler climes in the hills. Actually we hadn’t planned on going to Yeoor, but poor lunch service at Little Chef, an empty restaurant opposite Eden Woods, a housing society near Ghodbunder Road, left us with no option but to try out another eating place, this time in the Yeoor hills. I find crowded family restaurants overbearing, and relish any opportunity to eat in peace. Satish said he knew of one such eatery in the hills. “I’ve been there. It’s a good one, particularly the ambience,” he said. I agreed, at least the ride would be pleasant I thought.

Yeoor hills is the Thane-end of the National Park that stretches across the region to include parts of Borivali, along the terrain on either side of the Ghodbunder road connecting Thane to Borivali through Mira Road and Bhayandar.

The hills lie on the periphery of the wildlife sanctuary, and are populated by bungalows of sundry politicians and Muncipal Corporators along the route passing through the village. Much of this construction has taken place in contravention of law governing Adivasi land. The large-scale encroachment in the Yeoor hills, the exclusion of Yeoor from the wildlife sanctuary despite it being contiguous to the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, is seen as an attempt by politicians to protect their encroachments from coming under the purview of Acts governing forest land, and are a direct manifestation of the politics of power. All this was far from our minds as we rode up the hills, reveling in the temporary relief from the heat as we passed vegetation on either side of the narrow tar road curving up.

We took a right turn, onto a narrow road that branched off the main road and parked the bike beside a car, and walked across the open space fronting the restaurant, and crossed a small, wooden, arched bridge over a narrow moat and sat by its side so we could look at the few lotuses that grew in it. The water was still. Mid way through our meal I saw the old man with white hair and a pair of glasses across from where we sat finish with his meal, and smile at the waiter before leaning across the table to pick up a black case holding a musical instrument. He got up and put on his coat. I had first noticed him when we took our seats at the table. Something about him did not quite jell with the setting. He didn’t seem to fit in in the ambience of a lazy afternoon. I wondered if it was because of the way he dressed. Nobody wears grey suits anymore where I live and work let alone on a Sunday noon in the hills. Or maybe it had to do with the way he ate, concentrating on his food, rarely looking up, certainly not the sign of a man who’s dropped in for a bit of quiet. Seeing him eat marked him out as someone who was here for a definite purpose, and the purpose was not lunching out.

On enquiring with a waiter I learnt that he played his Mandolin for visitors. On the other side of the narrow moat, the restaurant has set aside a platform under an arch a little distance off the eating-place, and provided a sound system for performers to entertain clients. Jairam Mohite, 76, has been playing his mandolin at the restaurant for over two years now.

After Satish and I were done with our lunch, he came over to where we sat, and we talked the afternoon away, listened to tunes on his old mandolin of old hindi film songs from years ago when he worked with Laxmikant-Pyarelal, starting off with Parasmani in 1963 for which Laxmikant-Pyarelal composed the music. “I played for most of the Hindi films they set to music,” Jairam said. "

Parasmani was my first assignment with Laxmikant-Pyarelal."

His forehead set off a narrow, angular face, the kind of ruggedness a cigarette manufacturer might want to use for a cigarette commercial for people who've been smoking for over fifteen years. The glasses he had on reinforced it. It was the face of a man who’d seen hard times and lived to tell the story. It was not the face of a man who drank, and certainly not of one who’d shrink from whatever life threw at him, but it was not a happy face either. I got the impression he’d do what’s necessary to be civil to people who visited the place, and no further. The voice was sharp, even if not very fluent, and I might’ve expected a larger frame for someone with his voice.

“I was well built before,” he told me, “until my illness recently. My stomach used to swell. A doctor who used to visit this restaurant and listen to me play my mandolin noticed my absence on subsequent visits and asked the Captain here about my absence, and took my telephone number and called my home. My daughter took the call and told him that I was in the hospital and was serious, and there was no guarantee that I’ll survive.” Jairam smiled, fiddled with his Mandolin, and continued, “The doctor came to visit me at the hospital, met the doctor in charge, pointed to me and told the doctor ‘

isko khada karo’ (Get him on his feet) and offered to get me any medicines I might need. He is a very nice man, this doctor Indoriya. He treats the elderly, and gets them out of coma.”

Mohites are one of the 96 clans constituting the Marathas, marathi-speaking warrior-peasants native to Maharashtra. Under Shivaji’s leadership, the Marathas ruled over a substantial empire to the west of India in the 17th and 18th centuries before declining as a major power with the advent of the British in India. “I learned to play the mandolin and the guitar from Ramprasad

ji, Pyarelal Sharma’s father,” Jairam Mohite told us. “Ramprasad

ji used to teach us the saxophone using musical notations we’d learned to read. Pyarelal used to play the violin.” Then he smiled at the memory of the Laxmikant-Pyarelal score for

Solah baras ki bali umar from

Ek Duje ke Liye, intoning it while we looked on. The emotion he tried to bring to the song was evident in the effort he made to recapture its nuances in a voice clearly unsuited for any kind of singing, let alone old Hindi film songs but it sufficed to set the mood as Satish and I leaned forward to listen to him. Then, recollecting his early days as a musician in the film industry when songs were recorded at Famous Studio in Bombay Central, he said “

Woh din bahut acche thay (Those days were very good).” He lamented the quality of music compositions produced of late. “Artist

kalakar bahut acche milte thay.

Aaj ka condition

bahut kharab hai industry

ka.” (Good artists were available then, the condition of the film industry has deteriorated now). He said the Industry (as Bollywood film industry is referred by some) was good before, and that payment was good too. “Our payment depended on the grade of the instrument we played. Mandolin

ka grade

alagh hai, guitar

ka grade

alagh hai. This (pointing to his mandolin) was graded B,” he said, “Music directors used to prepare a list and assign grades to musical instruments. Then they gave the list to the Music Arrangers and we were paid accordingly.” He said that at any given song recording in the studio, musicians numbered anywhere between 200-400, of which violinists formed the majority. I tried to imagine a setting big enough to hold that many, and the control the musicians would have to exercise to remain in sync with the rest, wondering to myself, 'That many in one place?'

I ask him if most Music Arrangers were Goans. He nodded and said, “

Haan. Goa

ke violin

mein bahut thay pehle, bajanewaley. Even now they’re there but not so many.” (Yes. We had many violin players from Goa in the industry then. Even now they’re there but not so many.) Talking of old melodies, his face softened when he mentioned that he was one of the musicians recording for the song

Aye mere zohara zabeen from

Waqt. The Balraj Sahni-Raaj Kumar-Sunil Dutt-Shashi Kapoor 1965 multi-starrer was Yash Chopra's third film with music scored by Ravi. "The music of those old Hindi films were classy,

unke baathee kuch alag thee." Then, he talked of his role in the song recordings. “Music

jo hum log bajanewale hai na, woh hamare gaane se matlab kuch nahi. Humlog sirf notation

letey, bajatey aur nikal jatey,” he said. (We, musicians, didn’t have anything to do with the songs, we merely followed the music notations we were given, played accordingly, and left.)

“Music Director

dhun bitathey, notation nikalthey, arranger

ko detey. Arranger

aur Music Director

jahan woh recording

baantha hai aander wahan par un log rehtey hai. Wahan se pata chalta hai kaun teda jaata hai, kaun wrong

jaata hai. Wahan se naam leke un log baumb martey.” Then he mimics their call, “

arrey baab Jairam wrong

jaata hai tumara, jaara sambhal ke bajao bhai.” (Music Director sets the tune for the song, prepares notations and hands them over to the Music Arranger. Together they monitor the musicians from the recording room. They can easily spot musicians who go out of sync with the rest, and call out to them by their names. Then he mimics their call, Jairam, you’re going wrong, play the music carefully.) Then, he adds, “Everything is in the hands of the Music Arranger, but the Music Director is the main guy.”

Jairam Mohite joined the film industry at twenty after his father, Sonu Mohite, taught him to play the mandolin when he was eighteen. “I learned to play it, and have been playing this very mandolin since then,” he said looking at it fondly. “It has lasted nearly sixty years,” he said. I sensed pride in his voice whenever he talked of his mandolin. “

Usko durust bhi nahi kiya hai. It is the same as before. The only thing I’ve changed are the strings.

Baja bajake rough

ho jaata hai.” (I did not have to carry out any maintenance except for the strings because they wear out after continuous use). “My father was an accomplished musician. He handed over this mandolin to me and said, ‘

Yeh cheez bahut meethi hai. Dikhne mein kamzor hai par takat hai ismey’,” (This thing – mandolin - is very sweet. It looks very fragile but has strength in it.) Jairam’s father was gifted the mandolin by a Sardarji (a Sikh) as a gift and was asked to give it to Jairam. “It (mandolin) is not so much in use in Hindi films these days,” he said, adding, “In our days the mandolin was an important component of the music. Rehearsals took place at Laxmikant

ji’s house in Vile Parle.

Agar wahan (at the rehearsals)

mood

lagti tho recording

karte. (If the rehearsals set up the mood well, we’d immediately record the song at the studios). The guitar and the mandolin were the main instruments at the rehearsals.”

He also worked with Shankar-Jaikishen and Madan Mohan, legendary Bollywood Music Directors. “Madan Mohan

ghazal ke raja tha,” he said. (Madan Mohan was the king of ghazals). “His music was the ghazal type.

Woh aisa udtha phudtha kuch nahi. Madan Mohan

ji Peti (Harmonium, used in the Indian music genres: Bhajan, Ghazal, Qawwali, Folk music, and Hindustani music.)

lagakey baaitthey they, dhun nikalneko. I worked with him on three occasions.” (Madan Mohan’s music was not light and playful. His was the ghazal type. He would sit at the

Peti to set the lyrics to tunes). It was evident that he held Madan Mohan in high regard. He said that Madan Mohan’s music was difficult to execute and that one had to be a master to do it. “

Uski jo chord rhythm

hoti, chord

bola tho mithasi lagna chahiye, Sa udhar hai, Pa neechey aata, Da udhar hai tho Ga neechey jaata. Upar-neechey, upar-neechey aur control

mein,” he explained as he nearly broke into a hand-dance tracing the rapid shifts in rhythms from low to high, and sideways that executing Madan Mohan’s music demanded. (Madan Mohan’s chord rhythm lent a certain melody to the composition, and was difficult to render. The

Sa would be over there, and

Pa below, then

Da over there, and

Pa would be down there. Up, then Down, Up again, and then Down.)

Sa,

Re,

Ga,

Ma,

Pa,

Da, and

Ne are the first syllables of the seven swaras or notes in Indian classical music:

Shadjamam, Rishabham, Gandharam, Madhyamam, Panchamam, Dhivatham and Nishadham .

Watching him animated, I thought that if I were to imagine it were dark and strings with bulbs attached at one end were tied to his hands, I might just about see a visual representation of Madan Mohan’s music as Jairam made rapid movements with his hands to illustrate his narrative. In his own rustic way that somehow jelled with the hills beyond the restaurant, he had drawn us into his life, carrying us back in time even if momentarily.

I can still hear Jairam’s voice as I write this. It had a certain rasp to it. Age had turned it to staccato, and I believe it made it stick in my memory as a result. I suspect that he had to make an effort to converse in Hindi though I cannot be sure if he paused as much when he spoke in Marathi, maybe he did because it seemed to me that that was the way he spoke, haltingly, and suddenly fluent as a train of thought or memory took hold of him and lifted his enthusiasm another notch.

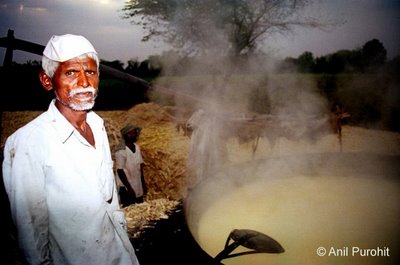

Basanna was clad in a dhoti and a Gandhi topi, the attire common to older generation of farmers in that belt. He’s been working on the farm for over twenty years and told us that sugarcane extraction begins post-Diwali. The kiln was set up at ground level over a largish area, now turned white with leftovers of crushed sugarcane. Underground piping carried the exhaust to a bottle shaped chimney about seven feet tall, constructed a short distance away from the heat source over which the kadai, filled with sugarcane juice was placed. The kadai held over 950 litres of sugarcane juice, a white simmering mass.

Basanna was clad in a dhoti and a Gandhi topi, the attire common to older generation of farmers in that belt. He’s been working on the farm for over twenty years and told us that sugarcane extraction begins post-Diwali. The kiln was set up at ground level over a largish area, now turned white with leftovers of crushed sugarcane. Underground piping carried the exhaust to a bottle shaped chimney about seven feet tall, constructed a short distance away from the heat source over which the kadai, filled with sugarcane juice was placed. The kadai held over 950 litres of sugarcane juice, a white simmering mass. We saw a few lined up along the length of the makeshift shed. It takes 950 litres of sugarcane juice to produce 11-12 such cone shaped blocks (called penti in the local language Kannada) of jaggery. Later they are shipped to the market. "950 litres of sugarcane extract will yield about 200 kilos of jaggery," Basanna said.

We saw a few lined up along the length of the makeshift shed. It takes 950 litres of sugarcane juice to produce 11-12 such cone shaped blocks (called penti in the local language Kannada) of jaggery. Later they are shipped to the market. "950 litres of sugarcane extract will yield about 200 kilos of jaggery," Basanna said.